Generational Amnesia

How a shifting baseline causes problems for all of us

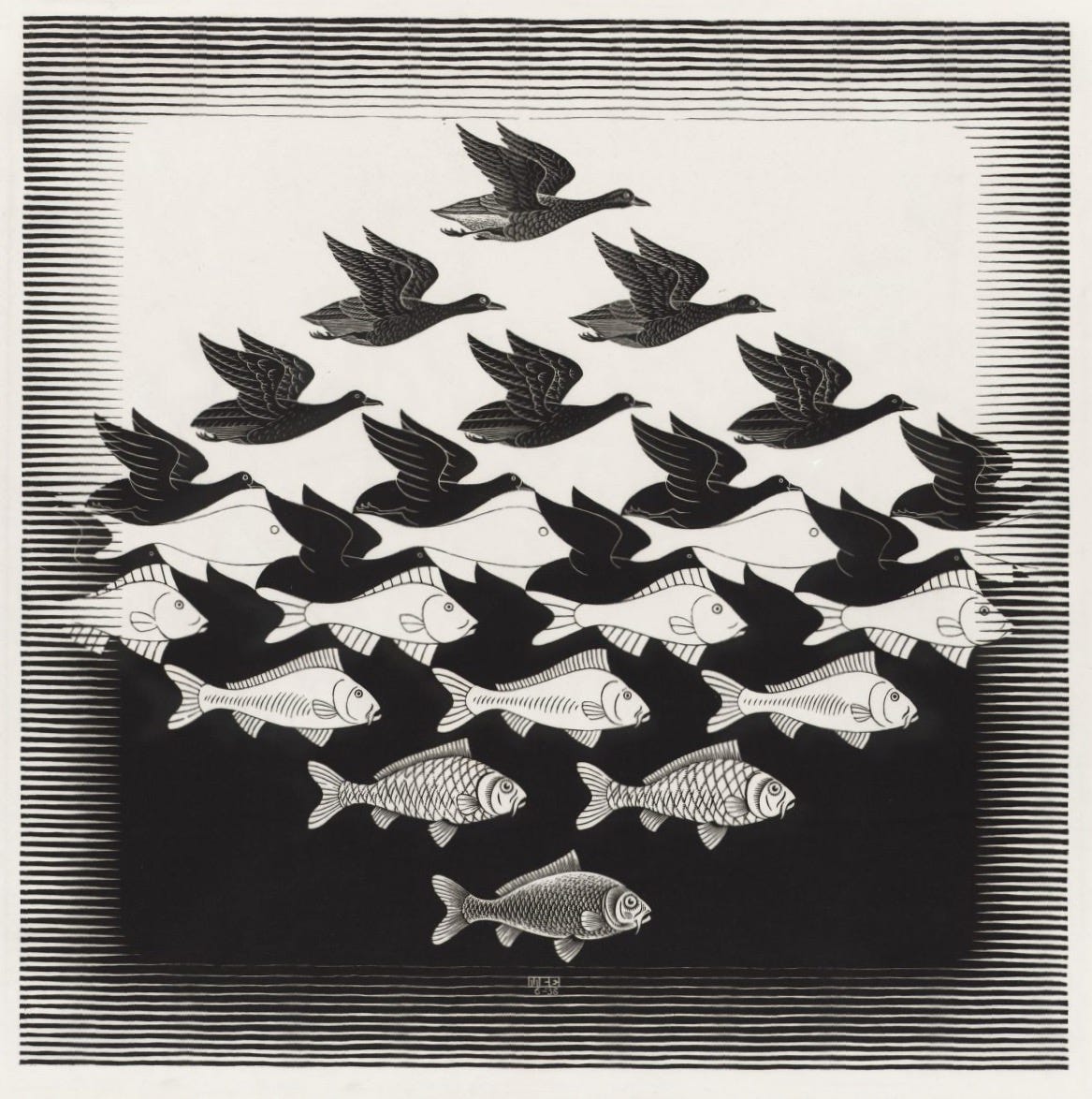

The Gradual Decline of Fish in the Sea and Birds in the Air

And the generational amnesia that follows…

“Things take time.” You’ve probably heard that since you were a child, and it’s true.

But sometimes things change so slowly that it’s imperceptible except across a time span of decades or lifetimes. This post is about the effects that take so long to happen, that it takes decades to recognize that things are going south. In many ways, rapid changes are easy—you can see when things go bad in front of your eyes. But when change takes many years, we can easily overlook it and not make the connection between the choice and the consequence.

For example, commercial fishing stocks have declined by an estimated 90% since pre-industrial times, but this happened gradually over decades. Each generation of fishers considers the depleted stocks they encounter as “normal.” What older Mediterranean fishers remember as common—six-foot bluefin tuna, the kind of fish you’d need a forklift to move—are now rare giants. Younger fishers think a three-foot fish is a good catch. And it is a good catch, given what’s out there. This “fishing down the food web” masks the true scale of marine ecosystem collapse and makes inadequate quotas seem reasonable. There is good reason to believe that biomass in the Georges Bank and nearby regions is 3-10% of what it was when large-scale fishing was started, declining slowly over 200 years. [Macintyre]

This is the problem of long, slow timelines. People tend to define “normal” as their experiences during their own lifetime. It’s only when you talk with previous generations that you realize there are slow consequences too. Climate change, the spread of megacities, the shift in animal or insect populations—each of these is slow, but the consequences are just as bad.

In 1995, Daniel Pauly described the “shifting baseline syndrome” and its problems for fisheries management. Pauly found that each generation forgets what fisheries used to be like, causing a kind of “generational amnesia” that allows successive generations to accept the current impoverished state of marine fisheries as normal. The generational forgetting of prior fisheries cloaks the changes in fisheries over the years, making it very unclear what the goals of fisheries regulation should be, or even could be. [Pauly]

This amnesia problem “..has arisen because each generation of fisheries scientists accepts as a baseline the stock size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of their careers, and uses this to evaluate changes. When the next generation starts its career, the stocks have further declined, but it is the stocks at that time that serve as a new baseline. The result obviously is a gradual shift of the baseline, a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species, and inappropriate reference points for evaluating economic losses resulting from overfishing, or for identifying targets for rehabilitation measures…” [Pauly]

Each generation of fishermen accepts the current fish population and size as normal, not realizing how much it has declined over time. For instance, in the 1950s, fishermen in the Gulf of Maine would routinely catch cod over 100 pounds. By the 1980s, a 50-pound cod was considered large. Today, many fishermen have never seen a cod over 20 pounds, and consider this normal. This gradual acceptance of diminishing fish stocks as the new norm has contributed to overfishing and made it harder to recognize the extent of marine ecosystem degradation. This is a story that has been repeated endlessly in fishery management circles. It’s especially difficult when the fishery has a long tradition with generations of local fisherfolk invested in the industry, all of whom face economic displacement when their preferred fish become impossible to find.

And it’s not even a recent story. In the pre-European colonization era of California, Native Americans would frequently dine out so often on particular species of birds (or fish, or mammals) that they would cause a localized extinction. In one notable study, researchers found that prehistoric San Francisco Bay dwellers would repeatedly eat specific kinds of birds into local oblivion, at which point they’d shift their attention to another kind of bird and then eat that species into extinction. [Broughton] First to go were the largest geese species—then the smaller geese—then attention would turn to scoters, then cormorants, then even smaller shorebirds. There’s little evidence that the bird hunters realized that their avian landscape was changing under their gustatory influence—as with shellfish in the Bay, hunters would shift from one prey species to the next as availability afforded. [ScienceDaily]

Most surprisingly, when European settlers arrived into the Bay area around 1776, they also imported a number of diseases that had dramatic killing effects on the local human population. [Ehrenpreis] The subsequent depopulation because of European diseases led to a massive reduction in hunting pressures on the bird population, leading to hyperabundance. In relatively short order there were large flocks of birds all around the Bay. [Preston]

“The wild geese and every species of water fowl darkened the surface of every bay ... in flocks of millions.... When disturbed, they arose to fly. The sound of their wings was like that of distant thunder.”

--George Yount, California pioneer, at San Francisco Bay in 1833 (from: The Chronicles of George C. Yount: California Pioneer of 1826) Charles L. Camp, George C. Yount, California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Apr., 1923) https://www.jstor.org/stable/25177691

This massive number of birds then became the expected baseline for wildlife populations. In fact, it was a kind of false Eden—the numbers were elevated because the original Native American hunters themselves died out removing any hunting pressures, only to be shortly thereafter replaced by European hunters which then caused their own particular kinds of extinctions.

Because birds are very visible, attractive, and easy to identify and count, reliable records have been collected over many decades in North America. Drawing on many different kinds of data for North America, it has become clear that there has been a long, slow, and wide-spread decline in the population of birds over the past half-century, resulting in the cumulative loss of billions of birds across a wide range of species and habitats. The overall loss of birds is not restricted just to rare and threatened species—but is commonplace across those all kinds of birds.

What’s caused this gradual decline? It’s what you’d expect: Habitat loss, climate change, unregulated harvesting, electrocutions, oil spills, collisions with human-made structures such as vehicles, buildings and windows, power lines, communication towers, and wind turbines. All told, this is massive bird death by a thousand cuts—any one cause isn’t the problem, it’s all of the causes of bird mortality that combine to a slow, gradual loss. [Loss]

We barely notice this today. Your grandparents might remember back when huge flocks of birds would drop onto agricultural fields, or when they would pass by in migration flights in their thousands. But it’s difficult for us to perceive the change with our limited life spans and distracted attentions. It’s a real effect that makes it difficult to plan wildlife management strategies. And it brings up a key question for our consequences analysis. When we finally see the result of a long, slow change with real consequences, what is the right response?

For shellfish the question is fairly simple.. or is it? Should we try to restore the species and population of shellfish in San Francisco Bay to pre-European contact numbers? What about geese in the Bay area? Should we plan to restore Bay Area wild geese to their historic levels pre-European contact, or should we aim for a restoration that reflects the hyperabundance of the Spanish colonial era of the late 18th century?

A great deal depends on what you think of as “normal.” And that depends on when you happened to live in the region. What was normal 50 years ago might be very different now. Think carefully about what restoration might mean—even if we could restore buffalo to the plains states, how would farmers with vast crops of soybeans or wheat react to the presence of 50 million bison roaming between Alberta and Texas? Asking for a friend…

Generational Amnesia for Vaccines

On March 1, 1947, Eugene Le Bar, a 47-year-old American businessman, arrived in New York City by bus from Mexico City and nearly caused a medical disaster in the process.

He had a severe headache that aspirin wouldn’t touch, then developed a high fever and a strange, distinctive rash. Le Bar felt bad enough to be admitted to Bellevue Hospital on March 5. Because he had a smallpox vaccination mark on his arm, smallpox was initially ruled out. But on March 10th, Le Bar passed away after ten days of symptoms at Willard Parker Hospital for Communicable Diseases and after an intensive search for the diagnosis. [Weinstein]

Soon after, other people at Willard Parker Hospital began displaying similar symptoms. A 22-month-old baby named Patricia, a 27-year-old man from Harlem named Ismael Acosta, a worker at Bellvue Hospital who had contact with Le Bar, and a 30-month-old toddler named John all developed rashes that puzzled doctors. A positive diagnosis of smallpox was made on April 4, almost a full month after Le Bar first walked into the hospital with a headache, fever, and rash.

Realizing that much of the population was not adequately vaccinated against smallpox, later that afternoon, Israel Weinstein, the New York City Health Commissioner, held a press conference urging all New Yorkers who hadn’t been vaccinated since childhood to receive another vaccination. The city quickly established free vaccine clinics and provided doses to private physicians.

The situation escalated on April 13 when a second person died from the disease. Mayor William O’Dwyer called for all 7.8 million New York residents to get vaccinated and publicly received the vaccine himself to set an example. The city mobilized its police, fire, and health departments, along with hospitals, to provide additional space for the vaccination effort. Doses of vaccines available on-hand were wildly insufficient for the entire city, but by scrounging vaccines from other states and the military, rapid response vaccine clinics were set up in all police stations and public health facilities.

By April 15, epidemiological investigation revealed that all diagnosed cases were related, and the outbreak had likely been halted through “ring vaccination”— tracing the movements of patients and vaccinating anyone who had contact with them until all possible contacts had been vaccinated.

The response was remarkably swift and effective. In less than a month, over 6.3 million people were vaccinated. This massive effort is still considered one of the largest and most successful vaccination campaigns in history.

The 1947 smallpox outbreak in New York City serves as an example of effective public health response, demonstrating the importance of rapid action, clear communication, and public cooperation in the face of a health crisis. It also highlights the critical role of vaccines in controlling infectious diseases and offers valuable lessons for modern-day public health challenges.

In the aftermath of the outbreak, New York City and other jurisdictions reassessed their public health policies regarding vaccination and disease surveillance. The event highlighted the necessity for robust emergency response plans, including the need for stockpiling vaccines and establishing rapid distribution networks. The city’s health department had a real policy shift, and began to prioritize preparedness for future outbreaks, leading to improvements in disease tracking and response strategies.

The smallpox outbreak also spurred legislative changes at the state and federal level, including the reinforcement of vaccination requirements for school children. Prior to the outbreak, New York was one of only a few states that mandated vaccinations in schools, and even so, the smallpox vaccination level was inadequate to the threat. The crisis underscored the importance of vaccination as a public health measure, leading to broader acceptance and implementation of mandatory vaccination policies

Because so many people knew and feared smallpox, these changes to require vaccines were widely accepted. The vaccination mandate extended to other common childhood diseases as well—measles, diphtheria, smallpox, whopping cough, scarlet fever, rubella—all of which were widely known and feared by earlier generations.1

But after the introduction of effective vaccination programs, these diseases became so rare that the culture as a whole had generational amnesia and simply forgot about the terrible effects of the diseases. It only took a few more years for vaccinations to be called into question as problematic in and of themselves. [Craig]

The intentional result of federal and state vaccination policies was that fewer people got these diseases. The perverse consequence was that perceptions of disease risk shifted, making the vaccines themselves seem like the far riskier option to many people and pressures to eliminate or mitigate vaccination mandates increased. Perhaps most importantly, in the early 21st century, state legislatures increasingly enacted exemptions from school vaccination requirements, setting the stage for measles resurgences in 2015 and 2019.

It’s clear the generational amnesia can undermine the law’s ability to protect society at large. Vaccination laws and requirements capture insights that transcend generational forgetting. This syndrome arises when a legal program, like a school vaccination mandate, so successfully eliminates a societal problem, that citizens, politicians, and lawmakers forget that the program is in fact still working to keep that problem at bay.

This generational amnesia, in turn, can lead to changes in law and policy that undoes the earlier work, allowing the earlier problem to re-emerge. After the vaccines are forgotten, more children get diphtheria or whopping cough and die.

More recently COVID-19 vaccination mandates have become almost uniquely politicized. While COVID-19 is too new to suffer from the shifting baseline syndrome, decisions are being made will give the regulatory shifting baseline syndrome more room to operate, undermining the public health gains made by making vaccine-preventable diseases much in the United States.

Until the late 20th century, for most people the risk of various dread diseases was sufficiently high that they embraced new vaccines. The intentional result of federal and state vaccination regulations was that fewer people got these diseases. The perverse consequence was that as perceptions of disease risk changed with forgetting, getting the vaccines in your arm seemed like a far riskier option to many people. Consequently, pressures to eliminate or mitigate vaccination mandates increased. Perhaps most importantly, in the early 21st century, state legislatures increasingly enacted exemptions from school vaccination requirements, setting the stage for measles resurgences in 2015 and 2019.

For example, the measles vaccine was created in 1954, becoming increasingly effective and distributed widely in the 1960s. Following the introduction of the vaccine, many countries began implementing mass vaccination. The World Health Organization (WHO) established the Expanded Programme on Immunization in 1974, specifically targeting measles. [WHO] These vaccination efforts dramatically reduced measles cases worldwide. It was such a success that by the year 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States.

However, in 1998 a fraudulent study published in medical journal The Lancet falsely linked the MMR (the vaccine that protects from measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine to autism. Unfortunately, this led to widespread public fear and misinformation, leading to decreased vaccination rates in some regions of the US.

Because government bodies started granting many different kinds of vaccination exemptions, predictably, outbreaks of measles (and other preventable diseases) began.

As vaccination rates fell below the threshold needed for herd immunity (approximately 95%), outbreaks began springing up in the U.S. and other countries. The resurgence of measles cases shows the challenges in maintaining high vaccination coverage amid vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, and brings up the even larger problem of keeping alive the knowledge of those dread diseases and how to use vaccines to eliminate them.

In this case, smallpox vaccinations stopped in the US after the disease was considered eradicated from the planet after massive WHO program to track down and vaccinate every last person on earth. The last person known case to have naturally acquired smallpox was three-year-old Rahima Banu from Bangladesh. She was isolated at home with house guards posted 24 hours a day until she was no longer infectious. Remarkably, she survived, and with ring vaccination and isolation, no more cases were reported. With Rahima, last known case of smallpox in the wild disappeared from the Earth. [CDC2]

Measles is different—there are a huge number of natural reservoirs of measles (such as the Middle East or Africa, where measles constantly circulates through the population), so the threat of recurrence is high. Like Eugene La Bar’s smallpox, people can move around the globe bringing measles with them. For such recurring threats, generational amnesia can be fatal. This is why laws requiring vaccination can capture a kind of medical wisdom that can transcend the years.

Getting a smallpox vaccination is no longer a part of childhood, it’s been taken out of the required trials and tribulations of childhood. A vaccine is a social requirement that protects everyone, even if you’ve never known anyone who has had measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, or pertussis.2

Widespread vaccination policies are a way of getting around generational amnesia, and helps us all avoid the perverse consequences of forgetting.

The Challenge of Remembering What We Never Knew

Measles has natural reservoirs. It hides in unvaccinated populations around the world, waiting for a plane ticket. When vaccination rates drop below the threshold for herd immunity, it comes back. For such recurring threats, generational amnesia can be fatal.

This is why vaccination requirements—and really, any regulations designed to prevent slow-motion catastrophes—serve a function beyond their immediate purpose. They are, in a sense, institutional memory. They encode the lessons learned by previous generations into structures that persist even after the lessons themselves are forgotten.

The problem is that institutional memory is fragile. Laws can be repealed. Regulations can be rolled back. Exemptions can be granted. Each change seems reasonable in the moment, because the baseline has shifted so far that the original state-of-the-world and the original danger seems theoretical.

Think carefully about what restoration might mean. Even if we could bring back the buffalo to the Great Plains, how would farmers with vast crops of soybeans react to fifty million bison roaming between Alberta and Texas? Even if we could return the oceans to their pre-industrial abundance, who would be willing to stop fishing long enough to let them recover?

The baseline has shifted. We’ve forgotten what normal used to look like. And perhaps the hardest thing about generational amnesia is that we can’t miss what we never knew we had.

But we can, at least, try to remember that we’ve forgotten something. We can notice when the fish get smaller and the birds get fewer. We can listen to the old-timers when they tell us how things used to be, even when their stories sound like exaggeration. We can look in the graveyards of our ancestors and remark at how many children perished of preventable dieseases. We can build institutions that remember for us—laws and regulations and requirements that encode the hard-won knowledge of generations past.

And when someone asks why we still require vaccinations for diseases no one gets anymore, we can explain: that’s exactly the point. The reason no one gets them is because everyone gets the vaccine. The absence of the disease isn’t evidence that the vaccine is unnecessary. It’s evidence that the vaccine is working.

The shifted baseline is a trick of memory, a cognitive illusion that makes every generation think their depleted world is the way things have always been. The only antidote is the deliberate act of remembering—or at least of building structures that remember for us, long after we ourselves have forgotten.And generational amnesia is a massive problem for any country that has large-scale problems that last for more than a few years. Thus far, the best remedy for the problems of generational amnesia are regulations that capture the knowledge of ages and provide lasting improvements in our behaviors.

In 1920, just 27 years earlier, there were around 110,000 cases of smallpox in the US. The chances were pretty good that you might have known someone with the disease.

However, Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis (DTaP, DTP, Tdap, or Td): along with 5 doses of Polio (OPV or IPV); 4 doses for Hepatitis B: 3 doses or the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella vaccine (MMR): 2 doses Varicella (Chickenpox). Each of these represents a disease that once terrified parents.

Broughton, Jack M. “Prehistoric human impacts on California birds: evidence from the Emeryville Shellmound avifauna.” Ornithological Monographs (2004): iii-90. https://content.csbs.utah.edu/~broughton/Broughton%20PDFs/Orn.%20Mono.%2056.pdf

[CDC] https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccine-basics/index.html

[CDC2] https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html

Craig, Robin Kundis. “The Regulatory Shifting Baseline Syndrome: Vaccines, Generational Amnesia, and the Shifting Perception of Risk in Public Law Regimes.” Yale J. Health Pol’y L. & Ethics 21 (2022): 1. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4028027

Ehrenpreis, J. E., & Ehrenpreis, E. D. (2022). A historical perspective of healthcare disparity and infectious disease in the native American population. The American journal of the medical sciences, 363(4), 288-294.

Loss, S. R., Will, T., & Marra, P. P. (2015). Direct mortality of birds from anthropogenic causes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46(1), 99-120.

Macintyre, Ferren, Kenneth W. Estep, and Thomas T. Noji. (1995) “Is it deforestation or desertification when we do it to the ocean?” Naga, the ICLARM Quarterly.

Pauly, Daniel. “Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries.” Trends in ecology and evolution 10, no. 10 (1995): 430.

Preston, W. L. (2002). Post-Columbian wildlife irruptions in California: implications for cultural and environmental understanding. In Wilderness and political ecology: Aboriginal influences and the original state of nature. Edited by CE Kay and RT Simmons. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, 111-140.

See also: Preston, W. (1996) Serpent in Eden: Dispersal of foreign diseases into pre-mission California. Journal of California and Great Basin. Anthropology 18:2-37.

ScienceDaily. “Early California: A Killing Field -- Research Shatters Utopian Myth, Finds Indians Decimated Birds” https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/02/060213090658.htm - summary of Broughton’s research.

Weinstein, Israel. “An outbreak of smallpox in New York City.” American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health 37.11 (1947): 1376-1384.

WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-measles-vaccination

Whopping cough (sic) looks bad. Haha. I think putting an idiot in charge of public health is terrible. A great article Dan. Thank You. jon A.