At the start of World War II, all kinds of ideas for novel weapons were being explored as ways to end the war.

Perhaps the most unlikely was Project X-Ray, an attempt to arm Mexican free-tailed bats with tiny incendiary charges that would cause a huge number of fires in Japanese cities that were mostly made of wood and paper construction.

The idea came from a dental surgeon, Lytle S. Adams, who had seen the vast clouds of bats flowing out of Carlsbad caverns. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Adams thought of combining the bats (which were numerous and considered something of a pest) with small, fiery charges that would go off after the bats were dropped from a plane. If (the reasoning went), the bats were dropped at dawn over a Japanese city, they would disperse in mid-air in a 20-40 mile radius. They would immediately look for a comfortable place to spend the daylight hours, roosting under eaves and in small spaces between wooden beams. Not long after landing, the timed fuses would go off, starting a short fire that might well set the building ablaze.

Lytle S. Adams had the idea, and also just happened to also be an acquaintance of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt after he flew her in his plane. Adams sent a letter with the idea to the White House in January 1942, just one month after Pearl Harbor, where it was passed onto the National Research Defense Committee.

They then forwarded the proposal to Donald Griffin, a young bat echolocation researcher, as related by Patrick Drumm and Christopher Ovre in this month's American Psychological Association Journal. Griffin, who later became a renowned psychologist who argued that non-human animals also possess consciousness, was quite enthusiastic about the idea.

"This proposal seems bizarre and visionary at first glance," he wrote in April 1942, "but extensive experience with experimental biology convinces the writer that if executed competently it would have every chance of success."

The President's men followed Griffin's lead. "This man is not a nut. It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into," a Presidential memorandum concluded. And so, just like that, a dentist's crazy idea about bats had become a U.S. government research project.

The U.S. military, intrigued by the potential of this unconventional weapon, began Project X-Ray in 1942. The Mexican free-tailed bat was chosen for the project due to its abundance, size, and weight-carrying capacity.

To make the project work, more than a few challenges had to be overcome. First, where do you obtain several thousand bats and how do you keep them fed? (They eat a huge number of insects each day, basically their entire body weight each night. You can’t just order 10 tons of flying insects from your local grocery store.)

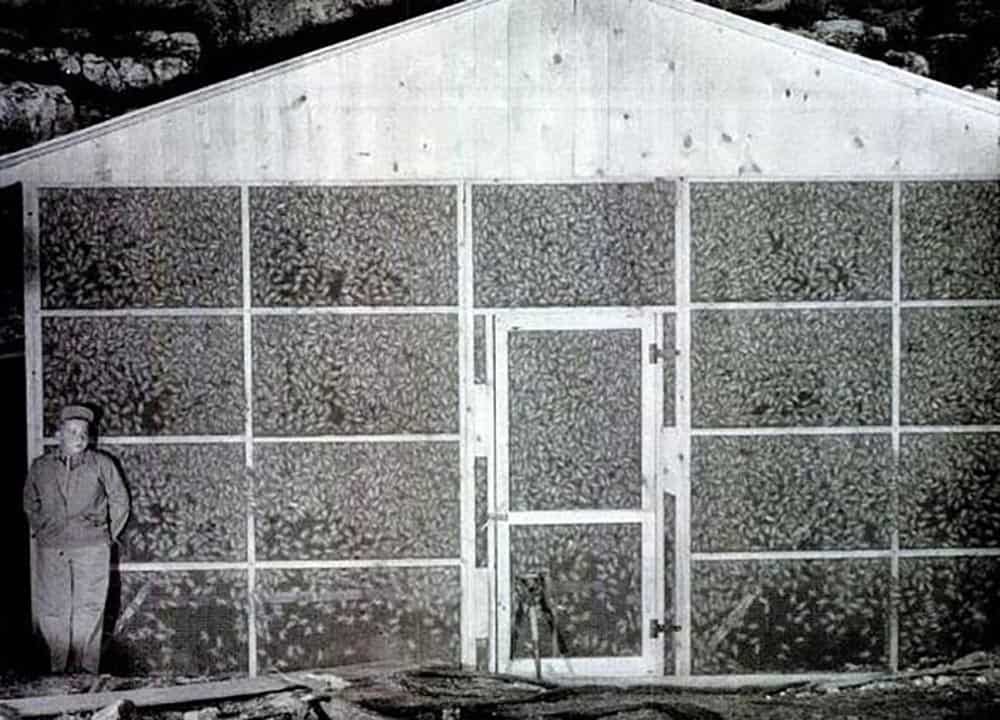

Bat house filled with Mexican free-tailed bats destined for bombing raids.

Then, how do you design an incendiary bomb that’s small enough for a bat to carry? Then, how do you get those bats + bombs to Japan and into a bombshell that will deliver them from a high-flying aircraft without killing them in the descent?

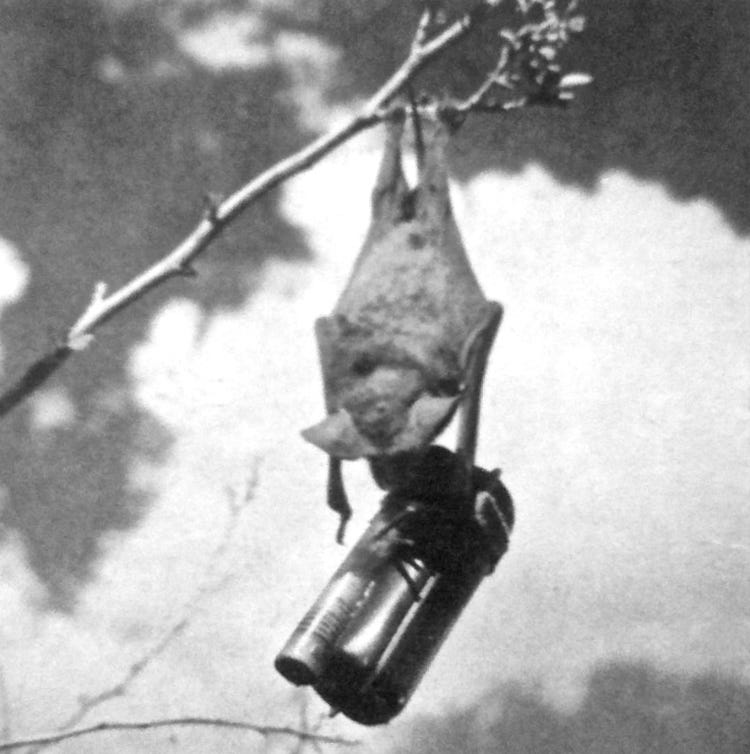

Tests determined how much napalm an individual bat could carry, discovering that a 14 g (0.5 oz) bat could carry a payload of 15–18 g (0.53–0.63 oz). The napalm was stored in small cellulose containers dubbed "H-2 units” gluing them to the front of the bats. Each had a minuscule triggering device that was supposed to be activated after the bats were released.

A bat with an H-2 unit attached by a clip to its chest.

The bats were delivered in a bomb carrier that was metal tube 1.5 m (5 ft) in length. Inside the tube was fitted with twenty-six circular trays, each 76 cm (30 in) in diameter. A single bomb carrier could hold 1,040 bats. The idea was that the bat carrier “bomb” would be deployed from an airplane, falling to an altitude of 1,200 m (4,000 ft) before deploying parachutes. The sides of the bomb carrier would then fall away, allowing the bats to fly away and seek shelter on the ground below. Since bats roost during the day, the bat bombs were to be dropped at dawn, just at the time when the bats would want to find places to hide.

Testing and Unexpected Consequences

The testing phase of the bat bomb project was filled with unexpected challenges and consequences. The first tests were conducted in a controlled environment, where the bats were successfully able to carry the mock incendiary devices. First problem solved.

After fairly successful research program and engineering development of the means to house and feed the bats, as well as get them into their tiny bat-harnesses with bomb attached and triggered, the testing moved to Carlsbad Army Auxiliary Airfield in New Mexico.

All went well until one disastrous test. The bats were armed with live incendiary devices and while being moved to the test site, some were accidentally released prematurely at the air base. Once freed, they naturally sought out dark and quiet places. At the Carlsbad base, finding such places was easy—at least one managed to find sanctuary under a fuel tank, causing a massive fire that destroyed several buildings on the test range and a general's car. One of those buildings also housed Adam's experimental records.

Carlsbad Army Airfield fire caused by escaped bats with incendiary devices attached. P/C Wikimedia.

You could argue that this was an outstanding demonstration of how well the program would work at the target location, but the accidental nature of the unintended firebombing (especially of the general’s car!) told some that working with wild animals was a bit too unpredictable.

Unlike conventional bombs, the bat bombs had enough intelligence to locate and occupy small places that were perfect for their incendiary mission. But unlike conventional bombs, if left alone and unconstrained for even a few moments, they would take off and cause unanticipated problems.

Moral of the story: Never leave your fireworks-laden bats alone; they can escape and find the most unlikely places to cause problems.

--

References:

Good summary of the entire bat-bomb debacle at Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bat_bomb

More details at Alexis Madrigal’s Atlantic story: Old Weird Tech: Bat Bombs of World War II.

The complete bat-bomb story with even more detail, by Eugene Burns and George Scullin: Project X-Ray